New algorithms allow scientists to simulate nanodevices on a supercomputer

By Nicola Nosengo/NCCR MARVEL

From computers to smartphones, from smart appliances to the internet itself, the technology we use every day only exists thanks to decades of improvements in the semiconductor industry, that have allowed engineers to keep miniaturizing transistors and fitting more and more of them onto integrated circuits, or microchips. It’s the famous Moore’s scaling law, the observation – rather than an actual law – that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit tends to double roughly every two years.

The current growth of artificial intelligence, robotics and cloud computing calls for more powerful chips made with even smaller transistors, which at this point means creating components that are only a few nanometres (or millionths of millimetres) in size. At that scale, classical physics is no longer enough to predict how the device will function, because, among other effects, electrons get so close to each other that quantum interactions between them can hugely affect the performance of the device.

Computer simulations can be the key to design these new nanotransistors, but so far the simulation of a realistic electronic device has remained out of the scope even for the most powerful supercomputers. The available computational methods could only simulate electronic interactions within structures made of a handful of atoms, while a nanoscale transistor includes tens of thousands at the very least.

In a recent work presented at International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage, and Analysis last November in Missouri by the MARVEL affiliated PhD student Nicolas Vetsch and now available in ACM Digital Library, a research team led by Mathieu Luisier from ETH Zurich and MARVEL has introduced a software package called QuaTrEx (Quantum Transport Simulations at the Exascale and Beyond), that combines in a new way different materials modelling methods. By running it on two supercomputers - one in Switzerland and one in the USA – they were able to simulate the behavior of a nanoribbon, the fundamental component of next-generation transistors, made out of over 42,000 atoms.

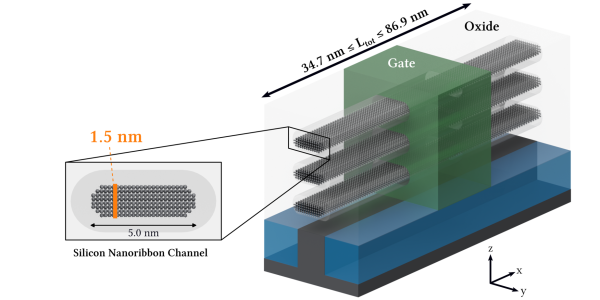

Schematic of a silicon nanoribbon field-effect transistor with three nanoribbon layers stacked on top of each other. The central ribbon was simulated by the team. (Image Credit: N. Vetsch et al. 2025

“A brute force approach to simulate such a physical system would not run even on the largest supercomputer” says Mathieu Luisier. “You need to speed up calculations on one side, and you need to find some tricks to reduce the memory consumption to be able to fit the problem on the machine”.

In their work, the team combined three computational approaches. The first one is density functional theory (DFT), the standard way to simulate the quantum mechanical properties of many classes of materials, semiconductors included. The second one is the GW approximation, that can correct DFT by introducing the relationship between electrons and the attraction or repultions forces they induce. This way it becomes possible to describe excited states with good accuracy, something DFT alone does not do. The third one is the non-equilibrium Green’s function (NEGF), that allows to add one more critical bit, namely modelling non-equilibrium phenomena such as the voltage-driven flow of electrons. The latter step involves the introduction of open boundary conditions in the simulation, that allow energy, particles, or fields to pass through the edges of a simulated area, mimicking real-world scenarios where systems aren't isolated.

The idea of combining these three techniques is not new by itself. “The first study that demonstrated it seriously was about 15 years ago, but it was a proof of concept on just a few atoms” says Luisier. “Using the same technique was never going to allow to model a realistic system”.

Two key innovations were made, explains Luisier. The first one is the calculation of the boundary conditions. “It’s a crucial step that we had to speed up, otherwise it would consume too much computing time”. Equally important is that the W in the GW approximation – the part of the computation that represents the forces induced by electrons - is also calculated using open boundary conditions, something that nobody had done before. Secondly, the team implemented a novel parallel algorithm to break down the simulation domain across different GPUs and make the best use of supercomputers.

The QuaTrEx package was run on the Alps supercomputer at the Swiss National Supercomputing Center in Lugano, and on the Frontiers machine at the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility in Tennesse, USA. The team used it to simulate various types of nanowire and nanorribon field-effect transistors, which have cross-sections of only a few nanometers. “We could not simulate the entire transistor because we did not have enough hours on the machine, though technically we could have done it” says Luisier. “Instead, we made a series of test to validate the numerical and physical accuracy of our tool. One of the largest device geometries we could simulate contained 42,240 atoms and was very similar to transistors that were actually fabricated by the semiconductor industry.

The research has made the team a finalist in the 2025 ACM Gordon Bell Prize, a major award in the high-performance computing community, where they were awarded an Honorable Mention (or second place) for reaching a sustained performance of more than one exa (1018) floating point operations per second. But Luisier says there is still room for improvement for QuaTrEx. “One direction we are considering is using what people call mixed-precision”, he explains. “Instead of representing all numbers with 64 bits, for example, you could represent some of them with 32 bits and speed up the calculation. The current GPUs which are optimized for machine learning use 16 or even only 8 bits to speed up calculations. This way our technique could become 10 times faster, but we would also lose accuracy, and we don’t want that. We’ll have to find a compromise”.

Another direction involves bypassing the need to use DFT at the beginning of the computation to calculate the Hamiltonian of the device. “That is expensive and can becomes a bottleneck if you want to consider more atoms” says Luisier. “In the future we hope to use machine learning techniques to predict instead of computing all DFT inputs, which would speed up the calculations even more”. Finally, the team would like to use their method to simulate logic gates, that are more complex circuits that can perform basic operations.

Reference

Vetsch, N. et al., Ab-initio Quantum Transport with the GW Approximation, 42,240 Atoms, and Sustained Exascale Performance, Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, 1-13 (2025) doi: https://doi.org/10.1145/3712285.3771784

Low-volume newsletters, targeted to the scientific and industrial communities.

Subscribe to our newsletter